|

| John, 2006 |

Winston-Salem native Bob Trotman is a self-taught sculptor working out of rural Casar, NC. Three of his charged busts were on display in 2011 at Blue Spiral 1's WOOD Moving Forward exhibition in Asheville, NC. Our conversation follows.

|

| No Brainer, 2010 |

JRun: Many sculptors seek emotional expression in clay, steel, bronze, or stone. How did you discover wood as an emotional medium?

Bob Trotman: I make everything in fired clay (terra cotta) before carving it in wood. The clay is where much of the creativity happens. I formulate my ideas in clay first and then cut and assemble the wood to realize the model.

|

| Studio Shot: work table with terra cotta maquettes, 2012 |

JR: Americana is certainly an appropriate association. Would you also describe your work as contemporary folk art?

BT: Folk art is usually attributed to the naive, and while I am self-taught, I am not naive. My work does have the populist tradition in common with folk art, though.

|

| Cake Lady, 2002 |

BT: I have said it represented an absurdist narrative of corporate purgatory, absurdist not because of an art movement, but because you would never see the sorts of things I am showing. I don't think that the greedy and powerful really suffer very often as a result of their misdeeds. So I try to take care of that in my imaginary world. It's not Expressionism. That involved much more distortion and crudity of fracture.

|

| Deskman, 2011 |

BT: I like the cracks (Wabi-sabi = the Japanese appreciation of the beauty of imperfection). I try to position the cracks so that they add to the emotion expressed in the piece.

|

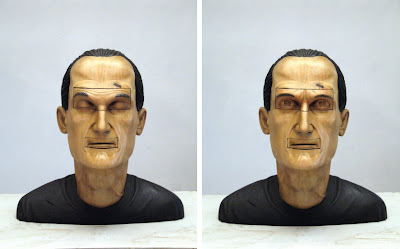

| Stu, 2008; Martin, 2008 |

BT: I use basswood and poplar. In the larger figures I use poplar (from logs) for the bodies and basswood for the heads, hands and feet. The smaller figures are all basswood. The poplar comes from logs I buy at local sawmills or cut myself. It cracks as it dries. The basswood, which grows in northern climes, comes on a big truck from a dealer in Charlotte. It is kiln-dried and must be ordered in lots of 1000 board-feet or more.

JR: When I look at your story, and your work, it is an inspiration and a reminder: that dedication and skill will stil pay off, even for an artist. There are labels thrown onto unsuccessful artists, especially in youth - immature, layabout, druggie, misfit, etc. And then there is the reality of the starving artist . . .

BT: ". . .dedication and skill will still pay off, even for an artist." I'd say, "especially for an artist." A good motto for the artist is: "They can't stop me from being an artist!" It is wise to be aware of the cliches about artists, which you mention, and do one's best not to accept them uncritically because they become self-fulfilling and self-defeating. There may be a niche that society puts you in, but you don't have to accept that. Part of being an artist is to create an independent sense of your own worth and not to passively accept what society may lay on you. You have to be proactive rather than reactive.

How do you measure success? Who decides that? You or them? Here again, you have to take charge. Nobody is going to do this for you. If you measure success as making a lot of money, you will perceive yourself one way. If you measure it as being able to live an interesting life doing work you like, you will see yourself in a different way. It may not be the way society sees you, but it is up to you to create the story that plays in your head. It's part of being an artist.

You start with the work you want to make. You make it for yourself. Everything else is secondary. How do you support that work? Day job? Teaching? Some combination? You have to figure it out strategically. "Work smarter, not harder."

JR: Did you struggle through poverty to get where you are today? Or did you fall back on a good day job to pay the bills and then burn the midnight oil on your art?

BT: From the very beginning I decided to keep my overhead as low as possible: to live where it was very cheap and sell where it was expensive. So my wife Jane and I fixed up an old farmhouse (no mortgage) out in the country, 25 miles from any town, and traveled to New York and other big cities for marketing purposes. At first we drew our water from a well with a bucket. Wood heat. Hand tools in the studio. That was the mid-70s, but we were hippies and it was fun, not a hardship. Not having grown up poor, 'poverty' was a novelty for me. I had been a teacher for a few years before that and had never really done physical labor. I found it liberating.

JR: Can you share any fresh work that shows your newest direction/excursion?

BT: Shaker, 2012, maquette, terra cotta. 7" long.

This may be scaled up and carved in wood eventually.

I am also beginning to make kinetic work. You might want to include this video of Minder:

JR: Where can we see your art in the future?

BT: My next big show will be at the Visual Arts Center of Richmond in 2014.

Thanks,

Bob

[Bonus Material: Inverted Utopias at the NC Museum of Art, 2010-2011]

No comments:

Post a Comment